One of Idaho’s First Charter Schools Plans Ambitious Expansion

When Jed Splittgerber’s oldest son was a baby, Jed assumed Milo would attend the nearby Boise public elementary school when it was time for kindergarten. “It’s a great school and our driveway touched its backyard,” he said.

But as Milo approached school age, Jed began researching options. And when he heard from a coworker about Anser Charter School in Garden City, it didn’t take long for him to decide the school matched his values to a T. Students directing their own learning. A strong sense of community. Encouraging productive failure.

“I value having my kids try a lot of different things, whether they’re good at them or not,” Jed said recently. “I see these third-graders doing public speaking and it blows my mind.”

So Jed entered Milo in the Anser admissions lottery, and they came up winners. Milo, who is now a third-grader at Anser, entered the school as a kindergartner.

Anser is one of Idaho’s first charter schools. Charters are public schools, free and open to all students. Anser opened its doors in 1999, serving 112 elementary-aged students in a vacant office building in downtown Boise. The school grew out of a series of visioning sessions led by Darrel Burbank, a Boise Public Schools principal who convened educators, parents, and academics to conceptualize a ‘dream school.’

The school was “founded on the lessons from geese,” according to the Anser website. “Our school would encourage students, staff, and parents to share leadership, encourage one another to fly higher, support one another when the going is rough and take responsibility for guiding the flock along new and challenging paths of discovery.”

As they searched for existing school models that matched their vision, their attention soon focused on Expeditionary Learning (EL), a school model developed in the early 1990s by the Harvard Graduate School of Education and Outward Bound, a leadership program based on challenging outdoors and wilderness experiences.

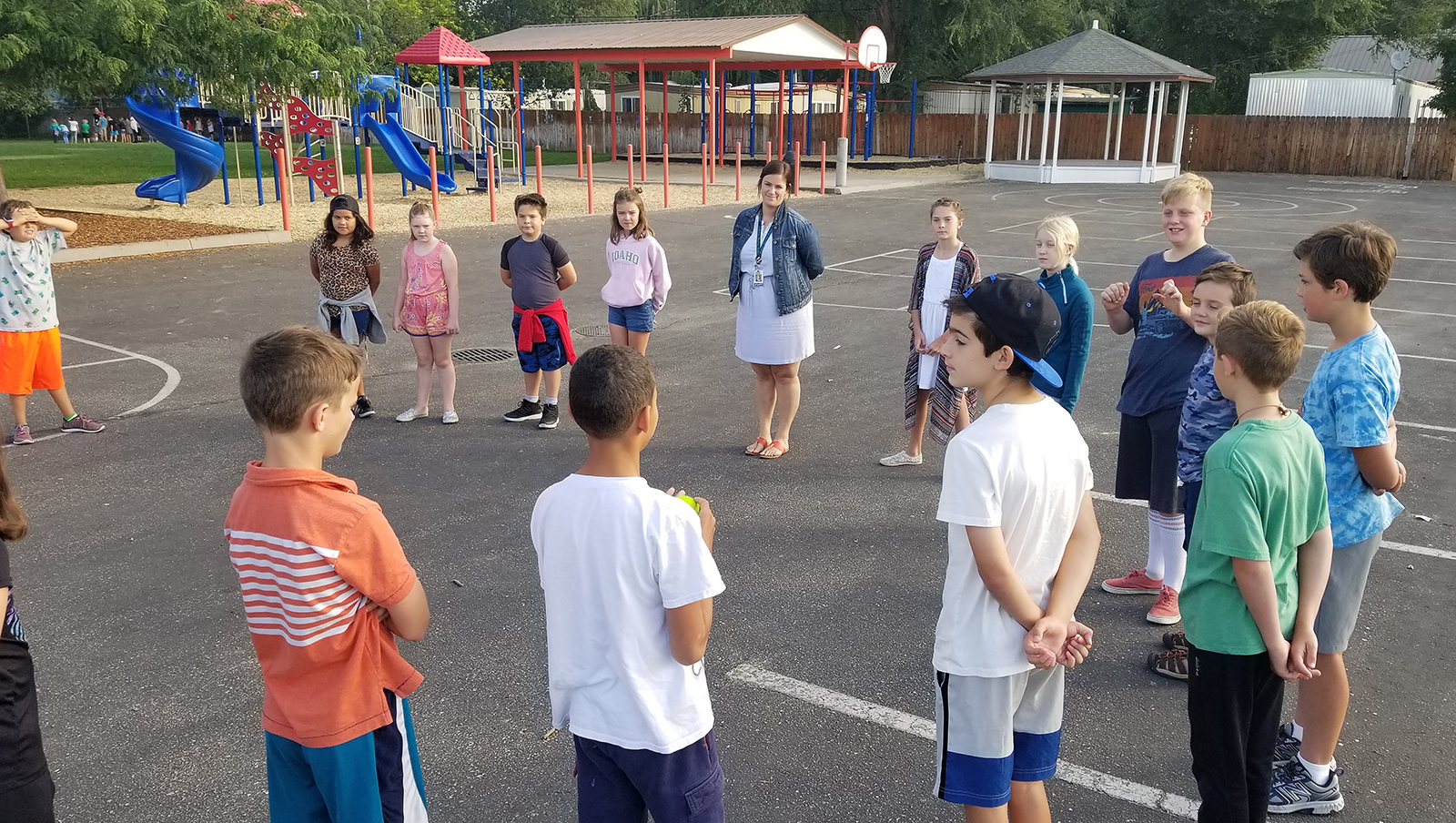

EL schools, now numbering 152 in 30 states, focus on student self-discovery through challenging academic curriculum grounded in real-life experiences with a heavy emphasis on time outdoors learning in nature. Students also take greater ownership of their learning than is common in a more conventional school.

“Learning is both a personal process of discovery and a social activity,” EL explains on its website. “Everyone learns both individually and as part of a group. Every aspect of an EL Education school encourages both children and adults to become increasingly responsible for directing their own personal and collective learning.”

Once Burbank and his coalition had drawn up plans for their dream EL K-8 school, they approached the Boise school district, seeking approval to open the school under district governance. They were rebuffed.

Fortunately, Idaho’s charter school law took effect in 1998, giving Burbank’s “Dream Team” another option for opening a school. They applied for a charter through the Boise district, and were approved.

The school has grown over the years. It now educates 375 students in grades K-8, in a Garden City facility Anser first occupied in 2009.

Anser is now embarking on another transition, with plans to grow and refocus its approach. In five years, the school will hold 675 students, still in the same K-8 grade configuration. This will require a major addition to the school building.

It has also meant a shift in charter authorizer. The Boise district wasn’t supportive of the expansion plan, so Anser applied for a charter through the Idaho Public Charter School Commission. The move from Boise schools oversight to the commission took effect in February.

Anser’s decision to grow stems from the educational needs of its students. Those needs have changed dramatically in recent years, according to Heather Dennis, Anser’s organization director — one of the school’s two co-leads.

Heather, Michelle Dunstan, Anser’s education director, and teachers began noticing several years ago that middle school students in particular were becoming disengaged from school, and were displaying signs of anxiety and depression. They were complaining that they didn’t see how school connected in any meaningful way to the ‘real world.’ All of this led to growing behavior problems and had a negative impact on the school’s culture.

This wasn’t unique to Anser. Educators from coast to coast have made similar observations about today’s students. At Anser, Heather and Michelle decided to take bold action to address these challenges.

“We decided to seek resources that would help us learn how to shift our program to better serve students, especially our adolescents,” Heather said. “We wanted to update our learning to be more future-ready. We are an EL school all the way, and we are not going away from our core practices. We’re going deeper into them.”

What this means in practice, Michelle said, is moving beyond student engagement into student empowerment. “We are not moving away from meeting the state standards, but students have more voice and choice and autonomy in how to get there,” she said.

Educators take more of a hands-off approach and guide students through the learning process instead of directing them. “Educators are letting go and letting students run with things. That might seem a bit chaotic at times,” Michelle said. “But in the end, the learning our students are experiencing through success and failure, my gosh. You can see the energy in the learning vs. the lack of engagement we were noticing before.”

To make all these changes work optimally for students means adding staff, and that means growth in student population as well. To plan and implement these changes requires time not normally available to school leaders. That’s why Heather applied for and received a Bluum Idaho School Leadership fellowship. She is spending this school year freed from her usual school duties to plan for the growth that is coming over the next several years.

“Even though we have never been a traditional school, even our practices need to shift based on what is going on in the world,” Heather said. “When I sit back and look at how we have done school for 150 years, to think that is going to prepare students for the future when we know what is coming is unfathomable to me. We are working under a moral obligation to shift how school looks because our world is changing so dramatically.”

–